Valentine’s Day —a day celebrating love, a thriving industry with billions of dollars spent on cards, flowers, jewelry, candy, dinners, and getaways, with murky origins in the third century execution of a Roman priest. The history of this custom is somewhat confusing to trace with three possible saints named St. Valentine and even more associated legends. One story has St. Valentine helping persecuted Christians by illegally marrying couples in secret; another tells the tale of when imprisoned and sentenced to death for these crimes, he signed his farewell note to his jailer’s daughter, whose sight he restored, “From your Valentine.” Nearly two centuries later in 469 A.D., Pope Gelasius declared February 14 as St. Valentine’s feast day.

The first known written association of St. Valentine with romance appears in Chaucer’s verses in the late 14th century, and the practice continued. Shakespeare’s Ophelia met Hamlet on St. Valentine’s Day, prompting her to think she had found her true love and sing “And I a maid at your window, To be your Valentine.” References are found not only in literature but also in the poetry of Charles, Duke of Orleans, written when imprisoned in the Tower of London after the Battle of Agincourt in 1415 and in the 17th-century diaries of Samuel Pepys, who recorded his special celebrations. By the 18th century, sending gifts, love letters, and handmade tokens to loved ones became a popular custom.

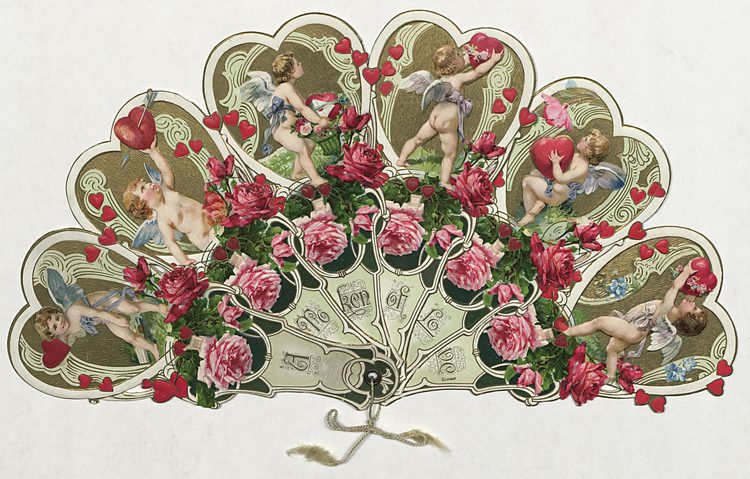

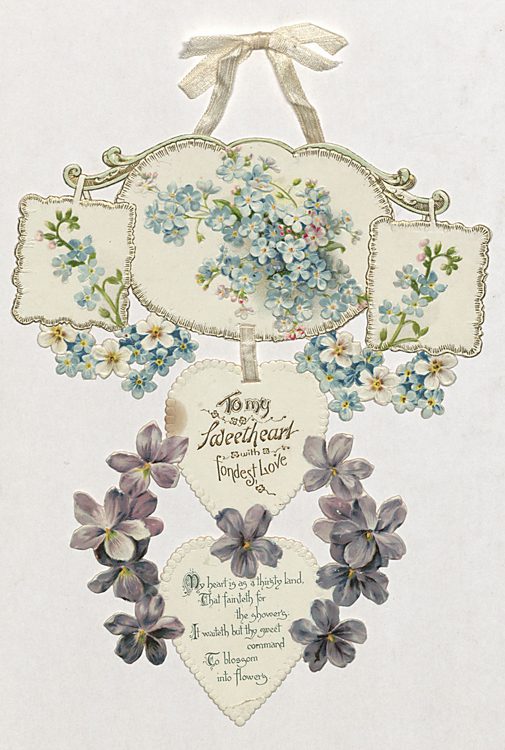

With later advances in papermaking and printing, mass-produced Valentine cards were manufactured starting in the 1840s and grew into a flourishing business for printers and stationers who increasingly offered an overwhelming diversity of items as decades passed. Beautifully designed greeting cards were also embossed, fringed, and made from a variety of materials and showcased images of cupids, adorable children, flowers, and loving couples. Novelty cards, even more elaborate creations, were advertised starting in the 1880s. Cards shaped into fans, hearts, diamonds, shields, musical instruments, horseshoes, and more were often decorated with fabric. Easels attached to the reverse of cards for semi-permanent display were “suitable for the parlor or boudoir.” Art-drop valentines featured several pieces joined by ribbons. Mechanical cards of different types were trendy; some pulled open with a string to reveal verses while others folded out to show multidimensional scenes made from several layers of paper and material.

After World War I, card manufacturers switched to simpler ones, but the tradition of sending cards continues with approximately one billion valentines sold today, second only to Christmas cards. Compared to these novelty cards from more than 100 years ago, our choices are somewhat tame. By nature transitory and made from cheap paper that has now become brittle, it’s astounding that numerous valentines have been carefully archived in the library’s Grossman Collection. Enjoy these examples of novelty cards and remember to acknowledge your loved ones.

In celebration of the season, we have reposted this blog post written by Jeanne Solensky, formerly the Andrew W. Mellon Librarian for The Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera at the Winterthur Library, now Librarian of the Memorial Libraries at Historic Deerfield.

The John and Carolyn Grossman Collection is a world-class collection of some 250,000 items that visually documents life in America, 1820– 1920.