This conservation lab is responsible for the care of collections in the Winterthur Library. The collections include books, manuscripts, printed ephemera, and photographs. Winterthur’s staff, outside researchers, and graduate students depend on these resources, so maintaining access while preserving the collection is a high priority. The collection includes 87,000 volumes of current and rare publications; more than 1 million manuscripts, printed ephemera, and photographs in the Joseph Downs Manuscript Collection; and 2,200 linear feet of archives, including manuscripts and archives.

Deterioration of library materials can result from poor environmental conditions, poor storage, and careless handling. High temperature and humidity accelerate chemical reactions that cause paper, photographs, and leather to deteriorate. Contact with poor storage enclosures such as acidic folders, unstable plastic, and corrugated storage boxes cause paper and photographs to weaken, discolor, and fade. Careless handling can cause torn, soiled paper and loose, broken bindings. Papers and leathers were poorly made quickly become brittle and deteriorated.

Preventive conservation

Preventive conservation is especially important for Library collections because the materials need to be used. The library stacks are maintained at 65 degrees and 45 percent relative humidity to extend the life of the collection. Researchers use book supports and other aids to help them handle collections safely. The librarians and conservators work together to provide protective enclosures for damaged collections and those in need of extra protection. Brittle or heavily used material may be reformatted to provide digital copies so the original can be retired except for those scholars who need access to the original.

Rare Books

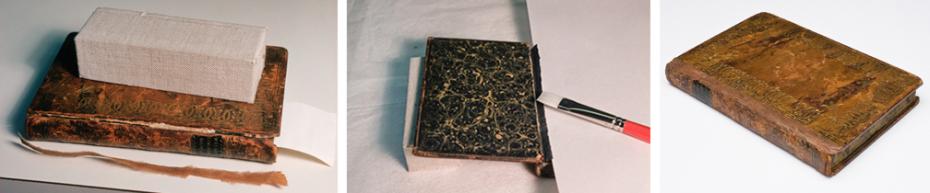

The collection ranges from 16th-century leather- and vellum-bound books to 19th-century cloth-case bindings and elaborate design books in finely tooled Morocco leather to trade catalogs in paper wrappers. Before 1800, most books were sold in sheets, then bound to the specifications of scattered booksellers and purchasers, so each binding is unique. In the 19th century, publishers began to bind books before they were sold, but often issued the same book in different bindings to appeal to different audiences. Each book and its binding in the collection has a story to tell about its time and place, so conservators repair and reuse original bindings whenever possible.

Thomas Wilson, dancing master, wrote An Analysis of County Dancing (GV1763 W75 S) for publication in London in 1808. In it he notes that “even persons of the meanest capacity” may acquire “a complete knowledge of that rational and polite amusement” and illustrates his instructions with woodcuts. The book was bound in a gold-tooled full-calf binding that afforded excellent protection for the text but succumbed to years of wear. The leather is worn and abraded and both boards are detached. Using toned, hand-made Japanese paper and reversible archival adhesives, the boards were reattached without compromising the original binding.

Object credit: RBR GV1763 W75 S Courtesy, The Winterthur Library: Printed Book and Periodical Collection

Manuscripts and Archives

The manuscript and archives collections contain everything from the daybooks of 18th-century silversmiths to late 19th-century tradecards for sewing machines; from architectural drawings for early 19th-century town houses to rare autochromes of Winterthur’s gardens; from photographs of Shaker communities to the exercise books of school children.

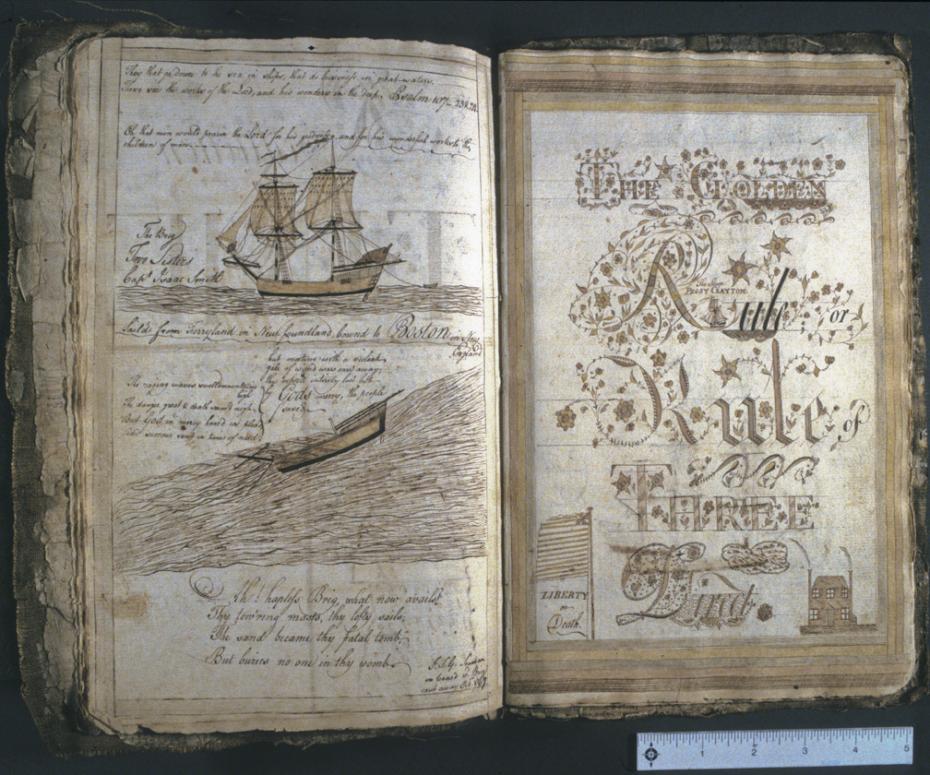

Peggy Clayton, who lived near Halifax, NC, created her calligraphy mathematics exercise book (Doc 1442) in the 1770s, ornamenting it with pictures of American ships, flags, and patriotic sentiments as well as standard exercises such as addition, subtraction, multiplication, rule of three, and simple and compound interest. She used the common writing materials of the period — hand-made laid paper, a quill pen and iron gall ink. The folded leaves were sewn into a soft cover composed of a canvas laminated between a heavy outer paper and newsprint on the inside.

The cover is detached from the manuscript and it is soiled, torn and dog-eared from years of use. Except for minor tears, the major problem is the unstable and corrosive iron gall ink. The acidity and related chemical reactions of the ink weaken and embrittle paper to the point where the paper splits or fragments in areas of heavy application, even when the paper is handled carefully. Research on processes to chemically stabilize the ink are ongoing but not yet ready for application to documents like this. To prevent additional damage, areas of severe corrosion needed reinforcement. Because moisture increases the rate of deterioration, standard mending techniques using water-based adhesives could not be used. Instead, conservators coated a thin, toned Japanese paper with an adhesive activated with ethanol to reinforce damaged area. This material is easily reversible and will not cause additional damage. After treatment, the manuscript returned to storage in climate-controlled stacks were the low relative humidity will slow the deterioration of the ink.

Object credit: Doc 1442 Courtesy, The Winterthur Library: Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera