Mark Catesby’s The Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands: Containing the Figures of Birds, Beasts, Fishes, Serpents, Insects, and Plants is the first comprehensive natural history work to appear in print. More than two decades in the making, and published in parts from 1729–1747, Catesby’s Natural History received praise as “the most splendid of its kind that England had ever produced.”

Although this work has been the subject of numerous scholarly studies, none have focused on Catesby’s specific color palette and pigment choices. The text that Catesby wrote to accompany each illustration included detailed descriptions of colors for each figure—flora and fauna. Are Catesby’s particular words for describing color matched by the color palette found in the illustrations? For example, when Catesby used the term “scarlet” or “bright red,” did he mean specific pigments?

Pigment analysis of a first edition of the Natural History in Winterthur’s library collection is under way in the Scientific and Analytical Research Laboratory, using X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF) and fiber optic resonance spectroscopy (FORS).

Study is ongoing and preliminary results are intriguing. The nuanced vocabulary is somewhat matched by application, where the “bright red” is red lead alone, which tends to orange, and “deep red,” “scarlet,” and “crimson,” are mixtures of red lead and larger portions of vermilion, as shown by the stronger XRF signal of mercury in these color mixes. The shades of red are sometimes visually discernable, as in the “bright red” of the “Red-bellied Wood-pecker,” identified by XRF as red lead alone. “Scarlet,” which is a mixture of red lead and vermillion, appears in the head of the “Gold-winged Wood-pecker.”

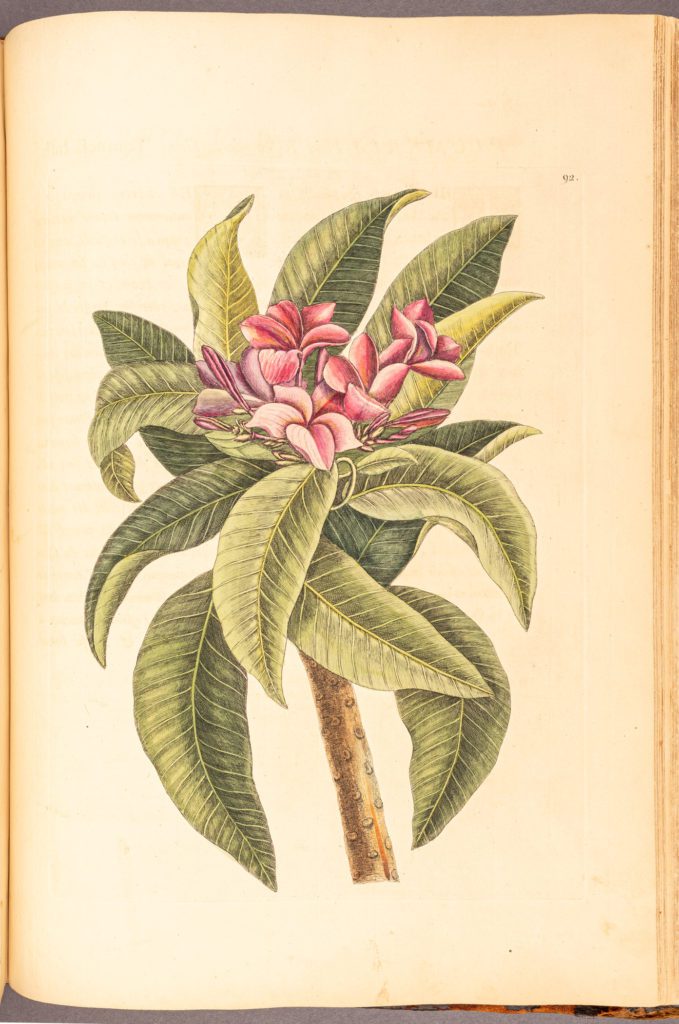

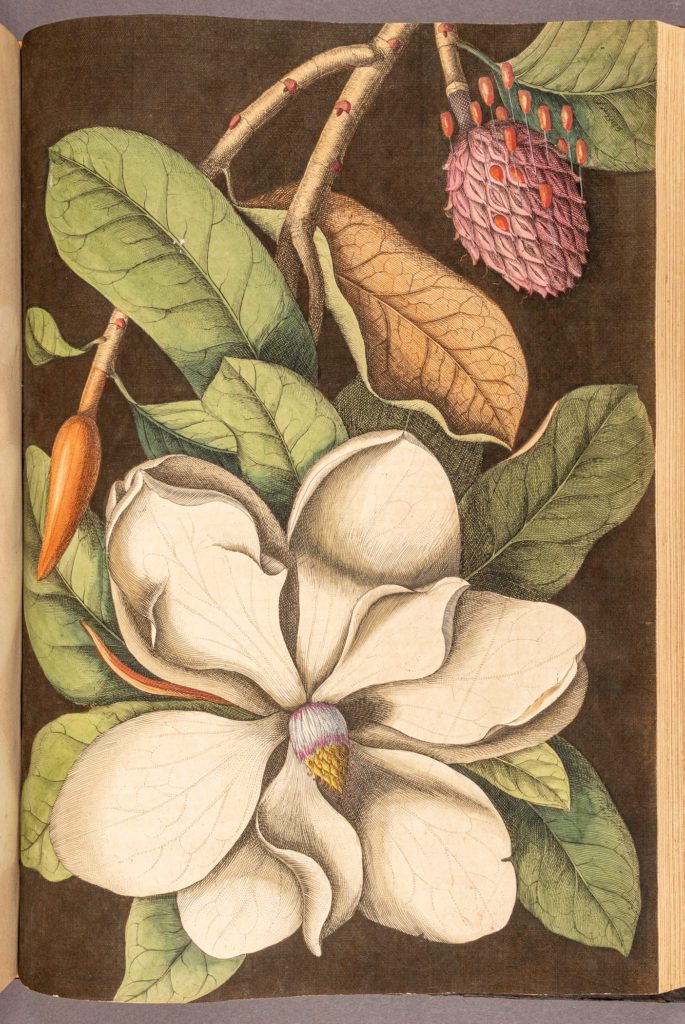

Scientists used a relatively new analytical technique, FORS, to identify the insect-based red colorant called cochineal, obtained from insects that live on cactus plants in Central and South America. Carmine, made from cochineal, was a vibrant colorant favored for tinting prints, likely because it was relatively inexpensive and easy to make. Catesby used the term “purple,” to describe this color, seen in the deep pink-purple hue of the magnolia’s seed pod. He used the term “rose” where he applied a vegetable-based colorant, likely madder, seen in the dark pink petals of the plumeria.

The volumes show a heavy dependence on body color or opaque pigments, particularly in the birds but sometimes in the fish and flowers. Colors such as massicot, red lead, white lead, and “liquid gold,” were generally used more often by the limner or miniaturist than the 18th-century print colorist. These mineral pigments, however, embodied the figures, especially the birds, with vibrant and durable color. Luminous, yet fugitive, transparent liquid color is occasionally present, most often in the plants, the map, and in very small touches, in a few birds. Together, these opaque pigments and liquid tinctures produced stunning, corporeal, representations of flora and fauna that may inform our interpretation of the works as illuminated prints, watercolor paintings, or an interesting hybrid of the two.