Some might think there’s a simple solution to saving outdoor sculpture that’s at the mercy of the elements: bring it inside. But H. F. du Pont wanted these particular sculptures—a pair of spectacular iron lilies—on display where they have been for decades, flanking the stairs to the Sundial Garden. Removing them from their location would betray du Pont’s design intent for this area of the Winterthur Garden.

Little is known about the manufacture of these objects. They’re estimated to have been created between 1860 and 1930, probably in New Orleans, and du Pont purchased them from the antiques dealer Churchill Brazelton in 1956.

We also know that they are unique— no other comparable sculptures are known to date. Each one stands about 5 feet tall and consists of meandering hand-wrought iron flowers, leaves, and stems embedded in concrete- and lead-filled bronze vases.

Despite routine conservation care, maintenance, and custom covers for the winter months, over time water infiltration has caused the concrete to expand. This exerts pressure on the bronze urns, cracking them in several locations. Staff has brought the sculptures inside temporarily to examine them and assess treatment options.

So why not just remove the concrete? It’s true that drilling into the urns, removing the concrete, and refilling with an inert material would solve the issue. But that is incredibly invasive, and it’s difficult to know how embedded the iron is within the concrete. It also runs the risk of irreparably damaging the urns, which are integral, original components of the sculptures.

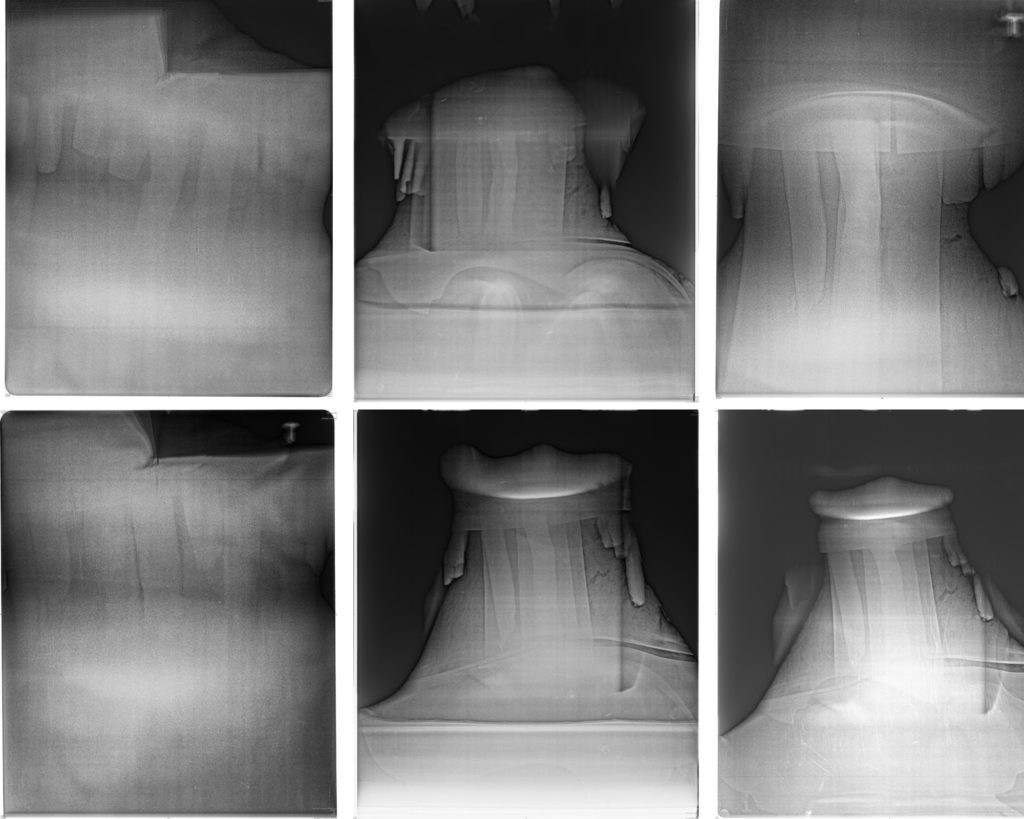

We needed to look inside.

Lauren Fair, Head of Objects Conservation, did just that. She X-rayed the sculptures, working with a team from Baker Hughes, supplier of the imaging software and scanner that Winterthur uses for its radiography. Though the concrete’s density made it difficult to see accurately into the sculptures, some answers could be determined.

“We can see clearly that many of the leaf elements don’t go down very far, but the main central stem likely does,” Fair said.

She and Rob Plankinton, Supervisor of Estate & Landscape, consulted on next steps with Adam Jenkins, a Philadelphia conservator who previously worked on the sculptures, and Warren Holzman, a Philadelphia metalworker. They concluded that the sculptures are entirely handmade, and the bases would be difficult to reproduce. Knowing this information and the radiography results, the team wants to avoid cutting into the urns. Fortunately, it appears that the base plate may be detached without causing significant damage.

Later this year, the sculptures will be transported to Jenkins’s studio, where they will be secured on their sides to access the inside from underneath.

Given the sculptures’ significance, we plan to update the public on our progress to preserve and return these beloved—and photogenic—decorations to the garden.

<can place caption at bottom of post – also pls credit any photographer who is not on staff>