By George Drake

Nowadays, a purchase at many stores concludes with the question, “Would you like your receipt emailed or printed?” But in 18th- and 19th-century America, the customer would often handwrite their purchases in blank books which would then be signed by the vendor to certify the transaction.

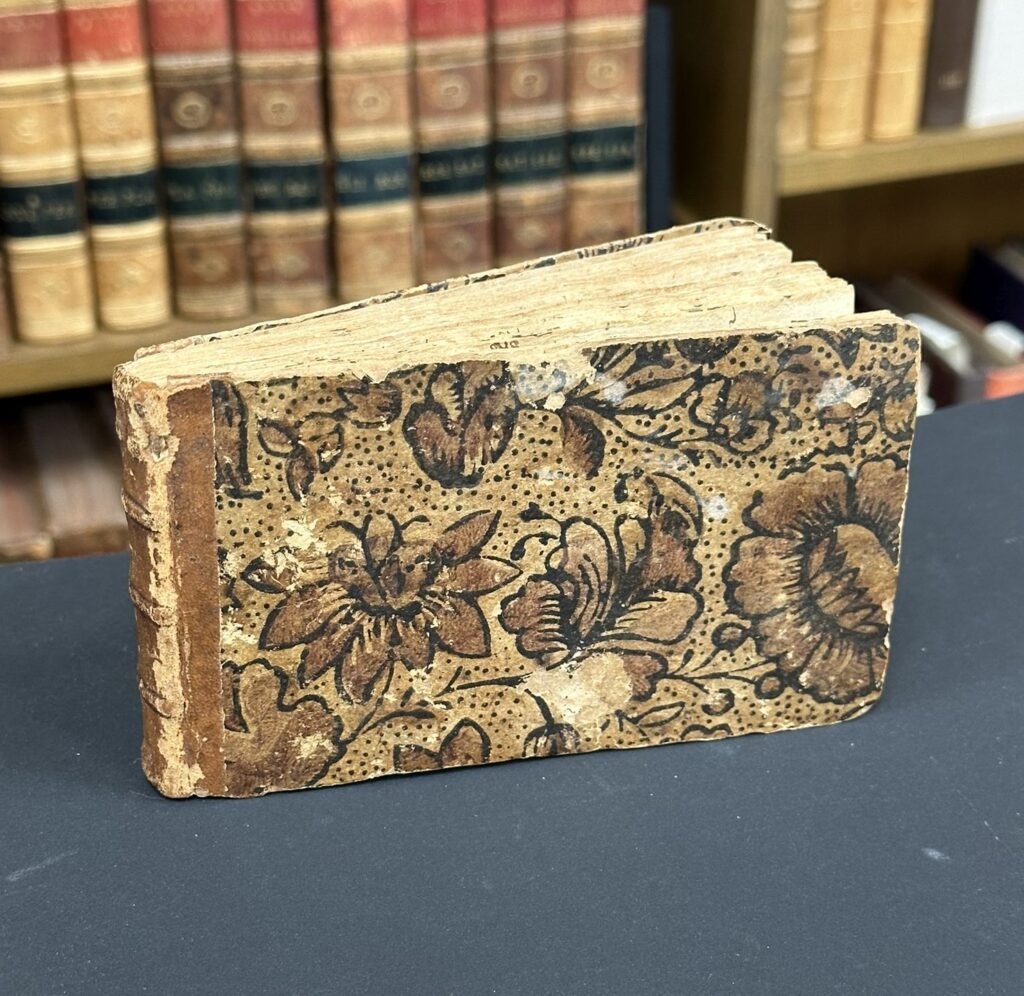

The Winterthur Library recently acquired an unexpectedly personal example of how receipts were recorded before every shop had a small printer on the counter. This Delaware manuscript receipt book is a pocket-sized, leather-bound volume used as a daybook from 1768 to 1853 by several generations of the Kendalls, a Quaker family from New Castle County, Delaware, and holds records for purchases and other financial matters.

Jesse Kendall (1741–1769) was the first to use the book. Jesse was born in Wilmington, Delaware, the son of a cordwainer (a shoemaker specializing in working with new leather). According to Quaker wedding records held by the Winterthur Library, Jesse was also a cordwainer when he married Mary Marshall in 1763. However, the 23 receipts he recorded between 1768 and his death in 1769 suggest he may have changed vocations at some point, since most of the receipts are for the purchase of molasses, rum, imported goods from Jamaica, and copious barrels of flour. Jesse’s final entry listed a payment of his taxes for 1768.

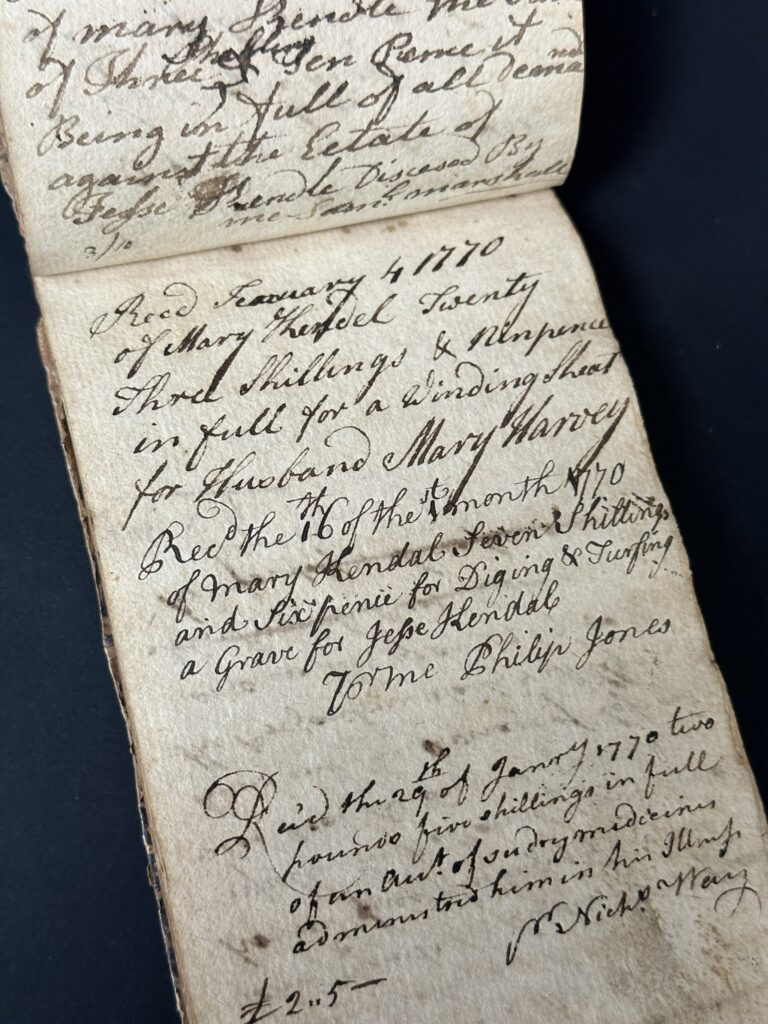

The end of Jesse’s life at age 27 is poignantly recorded in this same receipt book. His widow, Mary (1743–1802) used the volume briefly to record receipts related to the settlement of Jesse’s estate, funeral, and medical bills. Through Mary’s payment records of 23 shillings for a winding sheet for her husband’s body, 7 shillings for digging and “turfing” his grave, and medical expenses of more than £2 paid to Dr. Nicholas Way, we are given a glimpse into a difficult time for the Kendall family. Though the receipts lack any overt emotion, they invite us to reflect on the events behind the words. These records also situate the Kendall family in American history—less than two decades later, Dr. Way was a signatory on documents providing Delaware’s ratification of the U.S. Constitution.

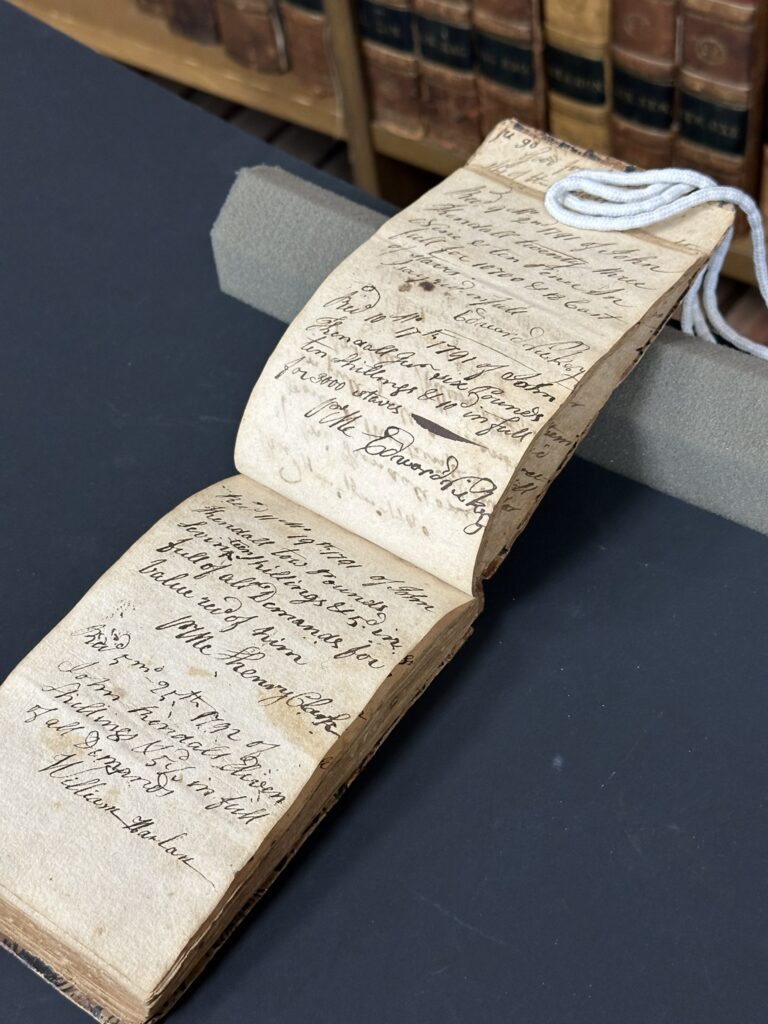

Jesse and Mary’s son, John Kendall (1766–1845), was the third family member to use the volume. His period of use was the longest (1789–1837) and the most diverse. Receipts include those for foodstuffs (e.g., oats, beef, and flour); goods (e.g., cow, watch, wagon, and staves); services (e.g., shoemaking, hauling, and carpentry); and financial matters (e.g., tax payments, interest payments, and estate payments).

The final member of the Kendall family to use the receipt book was Jesse’s grandson, Gibbons Kendall (1801–1864). He used the volume from mid-1852 to late 1853, over 80 years after his grandfather’s first entry. Instead of recording personal transactions as his predecessors did, Gibbons used the volume to detail financial transactions in the estate of his sister, Rebecca G. Kendall, who died on July 13, 1852.

Though it is impossible to know the day-to-day details of the Kendall family’s lives, this receipt book provides interesting examples of the macroworld of early American financial recordkeeping practices, and the microworld of one Delaware Quaker family.

Research into the volume is ongoing as part of the cataloguing process that new library acquisitions go through before being added to the library’s online catalogue, Wintercat.