Digitizing a unique and delicate manuscript makes its many mysteries accessible.

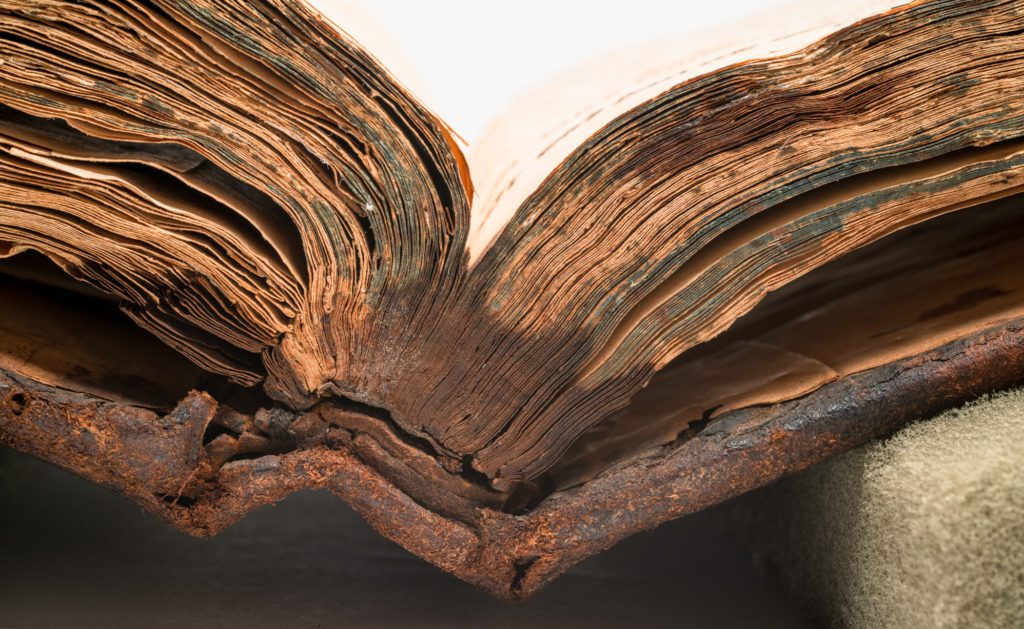

What does a museum do with a devotional manuscript too fragile to display? How do museum curators balance their responsibility to preserve with their commitment to accessibility?

Dr. Stephanie Delamaire, former Winterthur curator of fine art, contemplated these questions when the museum received the Denig Illuminated Manuscript, a gift from Alessantrina and David Schwartz and the Schwartz Foundation. This rare 18th-century devotional manuscript promises insights into the complexities of artmaking in the early American borderlands. “Our job,” says Delamaire, “is not only to preserve it, but also to curate it and make sure it’s available and relevant to a wider audience.”

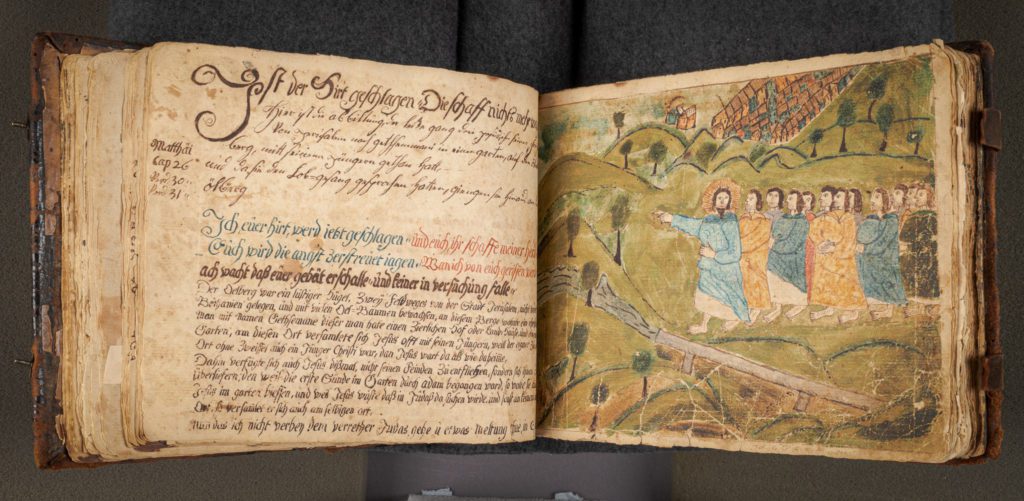

Bound in leather in the 1780s, the manuscript was created by Ludwig Denig, a Pennsylvania German man whose skills as a shoemaker and later apothecary likely played a part in the manuscript’s creation and binding. But Denig’s faith also left its mark on the manuscript. His Pietist leanings and his connections to both Lutheran and Dutch Reformed churches surface in the book’s hymns, personal and devotional texts, and ink-and-watercolor drawings of Biblical scenes and martyrdoms, which include events from the Passion of the Christ.

Fully experiencing the Denig Manuscript requires carefully leafing through more than one hundred pages of brittle, centuries-old paper. But each turn of the page threatens the integrity of the manuscript. To preserve this remarkable object while still sharing its story, Dr. Delamaire took a digital approach to its curation and interpretation. With the help of a grant from the Getty Foundation’s Paper Project and a grant from the Schwartz Foundation, Winterthur worked with the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media, a team of specialists, and community partners to create a digital platform that allows visitors to explore the manuscript’s contents in rich detail, with translations and readings of the text, professional recordings of hymns, and essays by leading scholars.

The digital platform also places the manuscript in the context of Ludwig Denig’s life and times. Denig created his manuscript during a period of conflict in the early American borderlands. He was born during the French and Indian War, a child at the time of the 1763 massacre of the Conestoga Indians in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, which took place within blocks of his childhood home. Denig also served as a private during the Revolutionary War. Could this proximity to violence have informed the contents of the manuscript? And what might Denig’s artistic practices reveal about early American traditions of artmaking?

The digital platform also asks key questions about the Denig Manuscript’s connections to Pennsylvania German fraktur, an artmaking tradition well represented in Winterthur’s collection. Denig’s watercolors bear similarities to fraktur, but they are also stylistically unique, distinguished by his attention to visual narrative in his depictions of Biblical scenes and martyrdoms. Denig’s methods also depart from those traditionally associated with fraktur. His broad washes of transparent watercolor, for example, contrast greatly with the dense applications of opaque color evident in so many examples of fraktur.

Though small in size, this remarkable manuscript may just hold the answers to many unanswered questions. “There’s nothing like it anywhere,” Delamaire says.