In 1815, when 14-year-old Ruth Wright embroidered her last stitch in the pale blue silk fabric that she had fitted around an 8-inch spherical form to make a terrestrial globe, did she feel a sense of accomplishment or relief, joy or frustration?

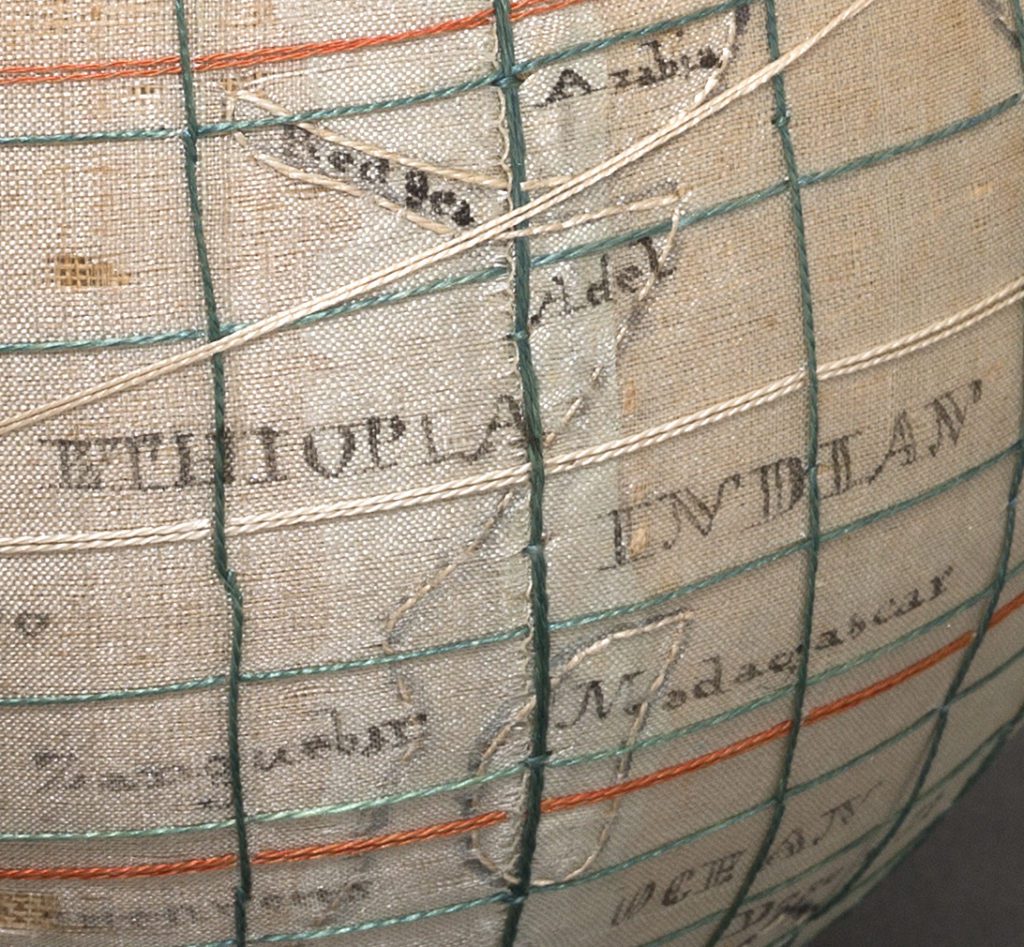

Ruth had sewn the skin of her globe sampler from eight pie-shaped pieces of silk on which she had carefully lettered in ink the names of continents, countries, islands, and oceans. After penciling the boundaries of countries, the equator, the Arctic and Antarctic, Ruth painstakingly embroidered the lines with fine white silk thread. She used red silk thread to delineate the tropics of Capricorn and Cancer and blue silk thread to mark the longitudinal and latitudinal lines.

The story behind the object

I am drawn to this piece because, in its simplicity and fragile state, it might not seem very attractive at first glance. But further examination and study of the history and makers of such objects can reveal much more. It’s the story behind the object—the why and the who—that interests me.

Because I started embroidering as a pre-teen, I feel some connection to the maker. I also lived and traveled as a child outside of the continental United States, and through these experiences, I learned to appreciate geography and cultures other than my own.

We do not yet know much about the young woman who created this piece. From a label on the bottom of the globe’s wooden stand and from her school’s records, we know Ruth’s name, that she was from Exeter, Pennsylvania, and that she made her terrestrial or globe sampler while enrolled for just one year (October 1814 to October 1815) at Westtown School in Chester County, a Quaker boarding school 25 miles west of Philadelphia. From research into the curricula at Westtown during this period and an examination of other known examples, we know the globe was both a useful study tool and a practical memento that demonstrated Ruth’s needlework skills and, perhaps more significant, the instruction she had received in astronomy and mathematical geography.

A rare example

Ruth’s terrestrial globe is among 40 known surviving examples of terrestrial and celestial embroidered globes made by Westtown School girls from the early 1800s through the mid-1840s. Enrollment records for documented globe-makers reveal that most girls attended Westtown for only one year during their early- to mid-teens and that they came from homes in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Maryland, and Delaware. The earliest Westtown embroidered globes date from an era when the few globes the school purchased for classroom use were made in England.

The silk fabric of Ruth’s globe is fragile and the colors are fading, but the piece is still useful as an educational tool. When not included in an exhibition at Winterthur or out on loan to another museum, it rests quietly in study-storage awaiting visits from researchers and special needlework tours. The globe was most recently loaned in 2016 to the Fenimore Art Museum in Cooperstown, New York, for inclusion in the exhibition, The Instruction of Young Ladies: Arts from Private Girls’ Schools and Academies in Early America.

Beth J. Parker Miller

Registrar