One need only look at the Port Royal Parlor at Winterthur to see what made Henry Francis du Pont a great designer.

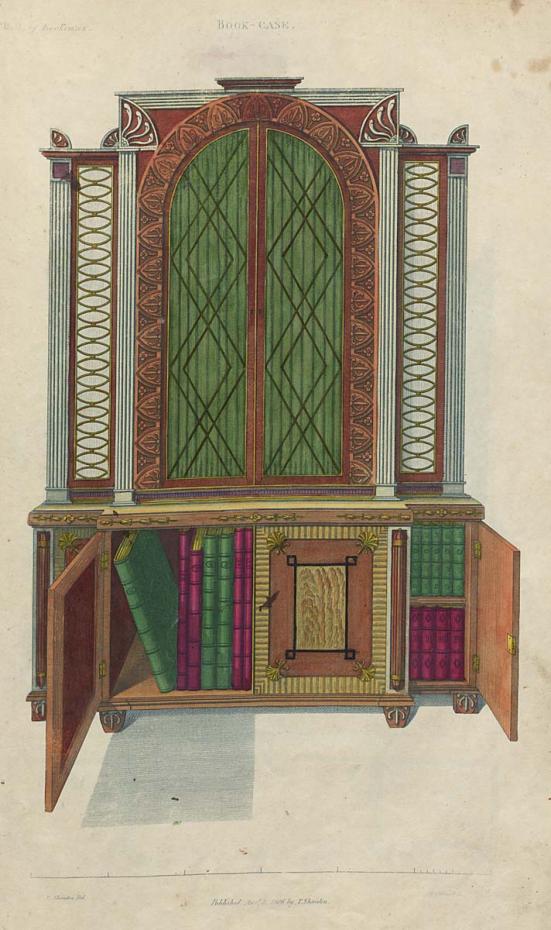

There is the prominence of color in the rich yellow draperies, sofas, and chairs, a vivid counterpoint to the jewel tones of the rug on which the furniture rests. There is the symmetry of the sofas, facing each other before the fireplace, as well as the side tables flanking the mantel, the high chests in conversation from their respective sides of the room, the chairs next to the chests, and the desk-and-bookcase centered between doorways. Among all this order, note the flowers. Even that touch is as carefully selected, beautifully arranged, and precisely placed as every other element of the room.

It is design of a type that is now so established, we barely give it a thought. But in H. F. du Pont’s time and social milieu, it was a new approach. He departed from what most designers of the day were doing and used American antiques as high style.

Understanding du Pont the designer begins with examining du Pont the collector, the focus of the exhibition Outside In: Nature-inspired Design at Winterthur. In his youth, du Pont collected things he found in nature, such as birds’ eggs and seashells. As an adult, his fascination evolved into a passion for historic American furniture and decorative arts—unlike most members of high society, who preferred to collect the arts and objects of Europe. His collection became a means to an end: the creation of beautiful spaces.

Du Pont collected items that were the highest quality of craftsmanship. He did not feel obligated to fill the many rooms of his home with furniture from the same period, place, or style, as a true antiquarian would feel compelled to do. He wasn’t trying to exactly re-create a Philadelphia room in 1780, for example. Rather, he used his collection as an artistic medium. He often placed items from different periods among sympathetic backdrops, using them to create a particular space.

He also incorporated different colors through the year, changing window treatments and slipcovers to harmonize with the light of the day and the changing seasons, as seen in his beloved garden outside the windows. It was second-order thinking that ensured every room looked stunning at every time of the year. Du Pont was truly remarkable—shape, color, textures, light—he thought through all that and put it all together.

He was highly influenced by friends and peers such as Electra Havemeyer Webb at Shelburne, in Vermont, and Henry Davis Sleeper, an interior decorator who turned his home into a showcase and helped du Pont design Chestertown House in Southampton, New York. Like his friend Dr. Albert Barnes, who assembled a world-class collection of Post-Impressionist, Expressionist, and folk art for his galleries in Merion, du Pont created settings that were not focused on a single object but on whole compositions. He also relied heavily on his friend Bertha Benkard, an authority on early 19th-century furniture who helped him select and buy pieces for his collection. He described her “faultless taste” as the reason he turned to her for advice on color and arrangement.

Yet du Pont’s aesthetic also differed from many of his friends’ preferences. Though he valued their opinions and sought their approval, he trusted his own intuition. The result was twofold: the creation of beautiful rooms and the legitimization of American objects as worthy of the treatment and esteem given contemporaneous objects from England and France. The vision that began at Chestertown House was fully realized at Winterthur.

H. F. du Pont was a trendsetter in his day. He influenced others to use American pieces in fashionable settings, blending traditional objects with a modern eye for color and display. He gave this design approach his stamp of approval, cementing it as being in good taste.