Hit enter to search or ESC to close

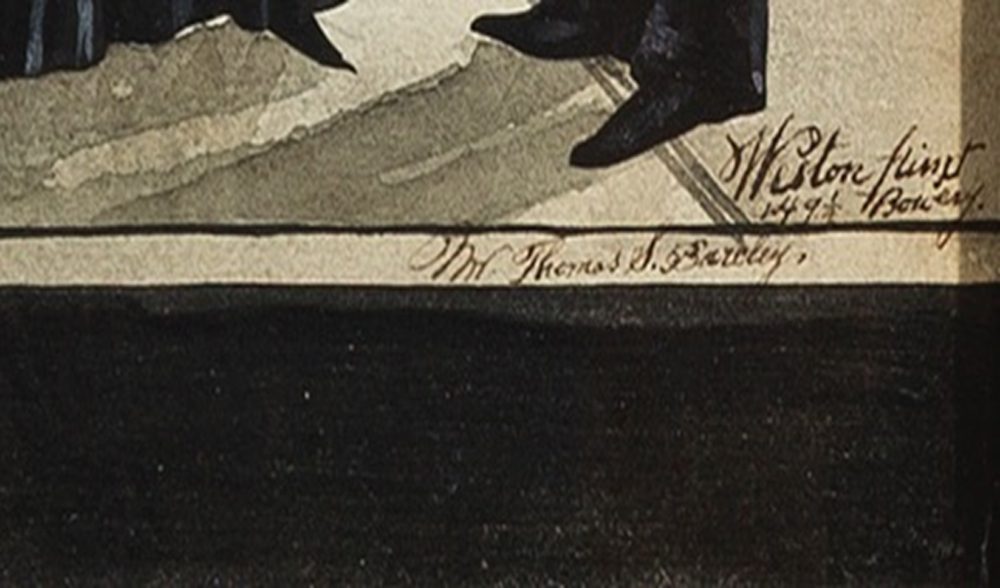

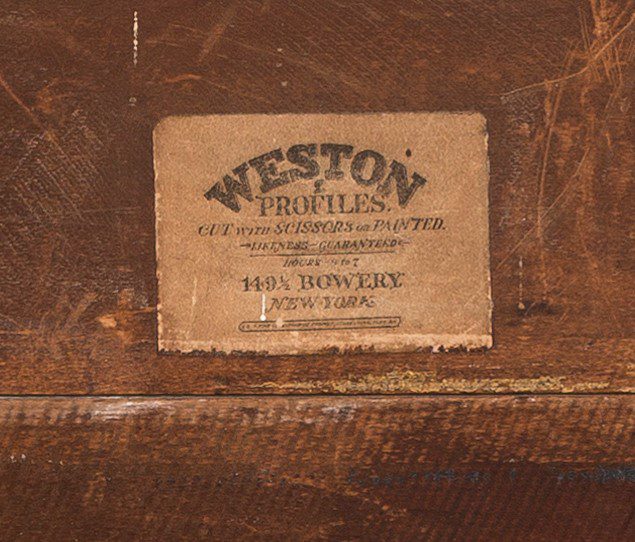

In the first Silhouette Sleuthing blog post, I detailed how I discovered that one of the silhouettes in the Winterthur collection had been misattributed to artist Mary Pillsbury Weston, who was most famous for her Spirit of Kansas painting exhibited at the Columbian Exhibition. There is no evidence to suggest that she ever produced and sold silhouettes. If the Weston profiles were not created by Mary, then who created them? I started to look through auction catalogs for other Weston silhouettes, hoping to understand the artist’s style. I found other pieces attributed to Weston, many of which are signed and contain the “Weston Profiles” label on the rear of the frame. Two types of signatures appear. The first, similar to the silhouette in the Winterthur collection, is a handwritten, cursive script with “Weston pinxt./149 ½ Bowery.” It can be found on a full-length silhouette of a woman, which was sold at auction by Northeast Auctions in 2015. (1) Other examples have a block-lettered serif signature “Weston of NY,” sometimes including the date. The two signatures could indicate that different individuals created these silhouettes under the name “Weston Profiles.”

Since most of the silhouettes have a “Weston Profiles/149 ½ Bowery” label attached to the back of the frame, it indicates that they have a common source. However, this does not solve the mystery of the address, since no Westons have been found at 149 ½ Bowery, as discussed in the previous blog post. Could these silhouettes be fake? Winterthur Paper Conservator Joan Irving examined the Weston profile in the frame, and there were no red flags to suggest it was not produced in the 19th century. However, she did note that the label appeared to have been cut down at some point. This does not mean that the silhouette is fake, it is possible the piece was reframed at some point and the label reaffixed to the new frame.

If we accept the material evidence that these silhouettes were made in the 1840s, and there are no known Westons living on Bowery at this time, who or what was at 149 ½ Bowery? The only reference to a 149 ½ Bowery found in primary sources is J. Wilson Fancy Goods Store listed in the New York Mercantile Union Business Directory in 1850. This reference seemed promising since a silhouettist could have operated out of a fancy goods store. J. Wilson, however, could not be traced to that location prior to 1850 in Trow’s New York City Directory. Looking at what businesses worked out of 149 Bowery during the 1840s, I found a distillery, leather working, and saddlery at this location. The leather business is possibly the closest connection, since cases for miniatures, silhouettes, and daguerreotypes typically utilized leather, and I found a group of Westons who operated a daguerreotype business in the city. This group of Westons can be found in the New York City directories during the period of production, and they include a John P. Weston, a Robert Weston, and another Mary A. Weston—all of whom were daguerreotypists. This was a promising avenue because the career jump from silhouettist to daguerreotypist would not have been surprising in the period. Silhouettes were a cheap, quick, and easy way to produce form of portraiture, some even employing the physiognotrace or pantograph machines, which are considered forerunners to photography. (2) Boundaries between what we understand as “fine artist” and “daguerreotypist” were fluid with some artists producing both artwork and daguerreotypes at the same time, and others using the technology to help with their artwork. Photography eclipsed silhouettes in the mid-19th century as a more accurate and equally easy method to produce mode of portraiture. According to the directories, James P. Weston operated in New York City as a daguerreotypist from 1842 to 1857. In 1842, James partnered with artist William Hendrik Franquinet to create a series of daguerreotype views of the city of New York and continued to work as a daguerreotypist throughout the 1840s and into the 50s. (3) Unfortunately, James P. Weston disappears from the records after 1857. The husband and wife pair, Robert and Mary A. Weston, were also in the daguerreotype business. The 1850 Federal census lists English-born Robert Weston as an artist, while the 1855 New York Census reports that he worked with daguerreotypes. (4) Mary’s profession is never listed in either census. Possibly blood relatives, Robert Weston and James P. Weston were listed together at 132 Chatham and 192 Broadway as daguerreians through the 1840s and 1850s. Mary Ann Weston was the daughter of British immigrant Thomas Kearsing (1774–1856), a pianoforte maker of the well-known Kearsing piano makers from the 1830s. She was born around 1812 in New York City, and she married Robert in 1839. She only appears in the directories between 1858 and 1861, where the couple were listed separately at 142 ½ Bowery. After Robert’s death in 1863, Mary continued to operate as a photographer at 392 Bowery until 1866, as seen in the U.S. IRS Tax Lists. (5) By 1866, Mary looked to move to California, posting in the New York Daily Herald: A PHOTOGRAPH GALLERY, ESTABLISHED IN THIS city in 1839, and in a flourishing state of business, to be sold as the owner must leave for California to settle some family affairs. Apply at WESTON’S Photograph Gallery, 392 Bowery, near Cooper Institute.[v] She eventually moved to California in 1874 to be with her siblings, where she died three years later. The Westons operated close to the 149 ½ address. Their closest relation to this address lies with a leather factory. In 1845, James P. Weston used the address 43 Eldridge for his daguerreotype submission to the American Institute and the Mechanics’ Institute Art Fair, an address he shared with Walter S. Abbott of Abbott & Smith Saddlery. Between 1842 and 1843, Abbott & Smith Saddlery is located at 149 Bowery. Did the two men know each other? Could Weston have operated a studio out of Abbott’s shop? Did Abbott make cases for Weston? These three Westons are the likely makers of the silhouette in the Winterthur collection. James and Robert exhibited works in the American Institute annual fairs. Robert submitted a “pen & ink drawing” at the 1846 show, (6) showing that he had the ability to produce at least the silhouette’s background. If Robert, his wife, and James were in business together, that could account for the different styles in signature and silhouettes that are found on Weston Profiles, i.e. block serif script versus cursive script. None of the silhouettes have a first name included in the signature but that is similar to the daguerreotypes produced by the Westons, which can be found in the New-York Historical Society, the J. Paul Getty Museum, and in auction houses. These pieces usually include the name “Weston” and the studio address across the bottom of the frame.

While research concluded that Mary Pillsbury Weston was not the creator of the Weston Profiles, another Mary Weston was most probably involved. The Westons produced silhouettes in the 1840s, and as the daguerreotype became more popular and more accessible to a larger market, they diversified by opening a daguerreotype studio. By the end of the decade and into the 1860s, they started to create photographs and carte-de-visites, continuing to stay abreast of consumer demands. They did not garner the notoriety like famous daguerreotypists Matthew Brady or Jeremiah Gurney, nor did they operate on their scale. In fact, New York City was filled with studios like the Westons’. In 1853, it was estimated that there were 86 portrait galleries in the city. (7) More research needs to be conducted on these smaller enterprises to get a better sense of the operations of a portrait-making and -selling business like the Westons’, and its relationship to a larger network of material production in mid-19th-century New York. You can see this silhouette and others from the Winterthur Library and museum collection in the special loan exhibition In Fine Form: The Striking Silhouette at the Delaware Antiques Show, November 9–11, 2018. Post by Amanda Hinckle, 2017-2018 Robert and Elizabeth Owens Curatorial Fellow, Museum Collections Department, Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library Winterthur is very grateful for funding from the National Endowment for the Arts, which has given us the ability to photograph and digitize works on paper in the collection, including these silhouettes. (1) Northeast Auctions. Fall Weekend Auction, October 31-November 1, 2015.Portsmouth, NH: 2015. Auction Catalog. https://northeastauctions.com/product/mary-pillsbury-weston-american-1817-1894-full-length-silhouette-of-a-woman-circa-1840/ (2) Emma Rutherford, Silhouette: The Art of the Shadow (New York: Rizzoli, 2009). (3) J Winchester, “Daguerreotype Portraits,” The New World: A Weekly Journal 5 (November 26, 1842): 351. (4) Although not in the New York City directories until 1848, the arrival of a Robert Weston is reported in the New-York Spectator in 1837, which is backed by immigration records. “Passengers,” New-York Spectator, March 28, 1837. (5) Craig’s Daguerreian Registry, last modified 1998, http://craigcamera.com/dag/. (6) New York Daily Herald, March 17, 1866, 7. (7) Ethan Robey’s dissertation titled “The Utility of Art: Mechanics’ Institute Fairs in New York City, 1828-1876,” includes an appendix listing artists who displayed their work. Ethan Robey, “The Utility of Art: Mechanics’ Institute Fairs in New York City, 1828-1876” PhD diss., Columbia University, New York, 2000. (8) Beaumont Newhall, The Daguerreotype in America, 3rd ed. (New York: Dover, 1976), 55.

This article was written in June 2017 by Natural Lands Intern Caroline Toth. Sadly, one of the goats that she portrays, Stanley, passed away at the end of August. This wonderful blog post offers not only a joyful glimpse into a little known world at Winterthur, but also timely solace to those of us saddened by the loss of a much-loved four-footed friend. Thank you, Carrie, for providing both.

As the weather warms and the meadow grasses flower, Winterthur’s herd of seven Boer goats is set to work munching areas of Brown’s Woods where invasive shrub-layer plants have taken over. Although our goats can’t discern between native versus non-native plants, the act of defoliation and damage to the non-natives suppresses the populations’ reproductive success. Plus, judging by our goats’ zealous appetites, it would seem that these greens are quite the delicacy, indeed!

It’s not always easy to get goats to do what you want, especially when you are introducing them to something unknown. When our livestock first saw the contraption we devised to transport them from pasture to forest, they harbored some serious reservations. Luckily for us, a mere handful of treats was compensation enough for them to voluntarily enter the cage strapped on to the trailer.

The “Who’s Who” of the Small Ruminant World All seven of our goats are purebred Boer goats. Originally from South Africa, the Boer goat was bred to be as large as possible to maximize profits in the meat market. “The bigger, the better” was the idea behind breeding Boers. Here at Winterthur, our Boers were all given to us as donations from herd owners who loved the goat in question so much that they could not bear to send them to market – and we are so glad, because now, we can’t imagine life without them!

Our first goats were Franklin and Stanley. Stanley is the alpha goat – kind of the wise caretaker of the herd. Franklin came from the same herd as Stanley, but Franklin is as loud as Stanley is quiet! Franklin is determined to make his presence known to every person and animal in the visual vicinity. When he is feeling affectionate, he lets you know by way of rubbing his head on you. When he is annoyed with you, he’ll emit a high-pitched whinny of frustration before slowly clopping away.

Morgan is a former show goat. Although she was born and raised on a meat farm, her good looks saved her from going to market. When she was pregnant with her kids, however, she developed a sway back. Around that same time, the tag on her left ear became stuck in a fence, and she ripped herself free, resulting in a permanently ripped ear. Because show goats are expected to be physically perfect, Morgan’s looks weren’t enough to save her anymore. We are lucky, then, that she had her babies Minnie and Missie. When Morgan’s previous owner saw how sweet they all were together, she donated the three of them to Winterthur to spare them a life of hardship.

Minnie and Missie are twins. They are now one year old – old enough to fend for themselves, in goat culture. But up until April, Morgan defended her kids with her life. She fiercely attacked any goat who came too close to her precious babies, and every human who came near was put under immediate scrutiny. Due to living such sheltered lives, Minnie and Missie developed exceptionally playful and affectionate attitudes. Although they now each fend for themselves, they still maintain the sweet and mischievous affectation they were notorious for when they were babies.

Nora and Riley are half-sisters who came from the same farm. Although they had different mothers, they were born around the same time. As kids, they bonded closely when both of them were donated to Winterthur in 2016. They are each fourteen months old – only two months older than Minnie and Missie – but they didn’t have their mothers around to protect them when they were smaller. Because of this, they had to learn to fend for themselves at an early age. Even though life is much more pleasant for them now, a youth of hardship instilled in them a quiet cleverness that still manifests itself every day.

It’s been a privilege introducing you to Winterthur’s goats! Just one glimpse of these creatures, whether out in the fields grazing or sitting atop their jungle-gym of giant tree stumps, will likely be one of the happiest sights you will see at Winterthur!

Although not currently on a tour, the Charleston Dining Room on Winterthur’s third floor contains woodwork and windows from what was once a fashionable gathering place in antebellum South Carolina. The 18th-century paneling, cornices, fireplace and mantel, and windows are from a hotel that stood in Charleston near the intersection of Broad and Meeting Streets. During its heyday in the 1820s and 1830s, the hotel hosted visitors from across America and Europe.

“Every Englishman who visits Charleston,” wrote one foreign guest in 1833, “will, if he be wise, direct his baggage to be conveyed to Jones’s hotel.” The Old World elegance of its dinners included iced claret that “might have converted even Diogenes into a gourmet.”(1) Another guest was Samuel F. B. Morse, who was then known as a painter rather than as an inventor. Around 1821, Morse came to Charleston and rented rooms behind the Jones Hotel to serve as a portrait studio.

Both guests would have spent time in the Charleston Dining Room. Located on the second floor of the hotel’s main building, it probably functioned not as a dining room but as a drawing room, where guests might gather after meals. The bay window projected over the main entrance on Broad Street, giving guests a clear view of city hall.

The Jones Hotel was also just a few hundred feet from the headquarters of Charleston’s city guard. After nine o’clock at night, the guard would arrest black residents, whether enslaved or free, who ventured out of doors. A German duke staying at the hotel around 1825 recounted hearing a warning call from inside his room, noting that he was “startled to hear the retreat and reveillé beat there.”(2) The Joneses, for all their importance to the social life of the elites—and although they were slaveholders themselves—were among the people being targeted.

What is now the Charleston Dining Room may be the only identifiable surviving part of the main hotel. The building fell into disrepair in the late 19th century and around 1928, it was dismantled and placed in storage. Some pieces, including the paneling in this room, were eventually acquired by the Yale University Art Gallery, where Henry Francis du Pont discovered them in the 1950s. The sections that made up the room were shipped from New Haven and installed at Winterthur, originally serving as a lunch spot for visitors taking all-day tours.

The warm sandy color of the walls is based on the earliest original layer of paint, applied around 1774 when the hotel was constructed as a private home. The white tiles lining the fireplace suggest the patterned Delft tiles popular in Charleston at the time. What comes from the building itself is the carved wood—including the windows, the elaborate decorations above the fireplace, and the two closet doors. The entrance, however, was moved from its original location opposite the bay window in order to fit the current space.

Post by Jonathan W. Wilson, a historian and adjunct faculty member at the University of Scranton and Marywood University.

NOTES

(1) Thomas Hamilton, Men and Manners in America, vol. 2 (Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood and T. Cadell, 1833), 278.

(2) Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar Eisenach, Travels through North America, during the Years 1825 and 1826, vol. 2 (Philadelphia: Carey, Lea & Carey, 1928), 7.

SELECTED REFERENCES

Amrita Chakrabarti Myers, Forging Freedom: Black Women and the Pursuit of Liberty in Antebellum Charleston (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011), 99–100.

Albert Simons, “Report of Matters Pertaining to the Removal of the Mansion House, Charleston, South Carolina,” n.d., Winterthur Archives.

Harriet P. Simons and Albert Simons, “The William Burrows House of Charleston,” Winterthur Portfolio 3 (1967): 172-203.

“Jehu Jones: Free Black Entrepreneur,” 1989, Public Programs Packet no. 1, South Carolina Department of Archives and History.

John A. H. Sweeney, The Treasury House of Early American Rooms (New York: W. W. Norton, 1963), 12, 76–77.

Marina Wikramanayake, A World in Shadow: The Free Black in Antebellum South Carolina (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1973), 79, 103–111.

For the first time in more than 70 years, a new monarch of the United Kingdom will be crowned on May 6—King Charles III. Objects commemorating coronations have been a tradition for hundreds of years, and Winterthur has many examples in its collection.

One of the newest is a remarkable hand-held panorama reel of King George IV’s coronation procession in 1821. The object reveals important information about the historic event and those who participated in it. Wound on a bobbin casing and housed in a wooden cylinder, the paper is pulled through a slot, which allows the holder to witness the procession in action. The panorama reel is on view in Conversations with the Collection in the first floor of the Galleries.

Ceramic mugs and plates are commonly created to commemorate a monarch or a specific event such as a coronation. A delftware plate portrays William of Orange (r. 1689–1702) and his wife, Mary Stuart (r. 1689–1694). The couple, who jointly ruled the kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland, is shown in an outdoor setting wearing their coronation attire, with the initials “W M R” for William and Mary Rex/Regina near their heads. This plate was most likely made in Bristol or London around the time of their coronation. Evidence of delft commemorative plates like this one have been found in America, particularly in New England.

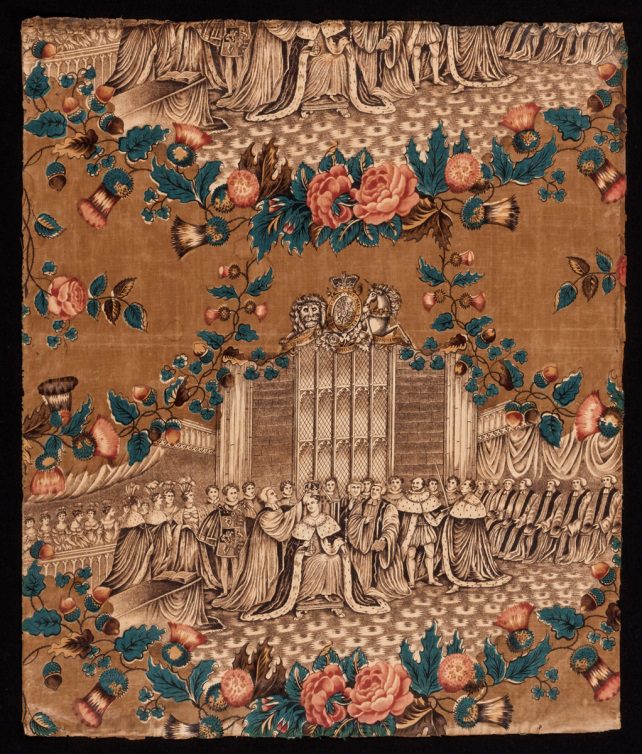

A more elaborate scene from the coronation of Queen Victoria in 1838 is featured on a printed textile in the collection. The swags of flowers that surround the scene resemble those used to decorate fabrics with American patriotic motifs. Evidence of patterns showing Queen Victoria’s coronation have been found in America.

The ceremony portrayed above hints at the richness of objects used during the coronation—the Crown Jewels, King Edward’s Chair, the Anointing Spoon, and much more. These objects are integral parts of the coronation ceremony and will be used on May 6 for King Charles.

The coronation of King George IV is also represented in the Campbell Collection of Soup Tureens by a pewter tureen, one of a group of table wares created for the banquet following the ceremony. The menu featured turtle soup, which may have been served in this very vessel. The Observer reported that crowds plundered the tables of the coronation banquet, taking the pewter dishes like this one marked for the sovereign. It bears the inscription “G IV R” below a crown.

One of the tureens that came to Winterthur as part of the Campbell Collection is from a group of pewter tureens and other tableware created for the banquet following the 1821 coronation of George IV. The banquet’s menu featured turtle soup, which may have been served in this very tureen. The Observer reported that crowds plundered the tables of the coronation banquet, taking the pewter dishes like this one marked for the sovereign. It bears the inscription “G IV R” below a crown. Unlike the objects above, which were souvenirs made for purchase, this object was made for use during the coronation festivities, and it was acquired by someone who decided to keep it without permission.

Post by Kim Collison, director of exhibitions

It’s 1919, and you have a one-year-old daughter. Delaware summers can be oppressive, and in the days before widespread air conditioning, there is not much relief. Where do you go to escape the heat? This was the decision faced by Henry Francis and Ruth du Pont.

They had many options—the beach, the mountains, or a European trip. People in their social circle tended to congregate in familiar places with family and friends. At times, it was as if the elite of a city was transported en masse to these summer retreats.

The extended du Pont family had no single destination, but Rehoboth Beach, the Chesapeake, Maine, and Fishers Island in New York all had their devotees. H. F. and Ruth du Pont made a different choice—Southampton on Long Island. Winterthur may have produced the happiest moments and memories for H. F., but for Ruth it was Southampton, where she had summered as a girl at her grandfather’s and uncle’s shingle-style houses with wide porches and green lawns. So in 1919, H. F. du Pont and family joined the summer colony there, renting a house for the season. In 1924 they decided to build and bought a choice piece of land along the dunes of recently opened Meadow Lane, situated between the bay and the ocean.

Having been inspired to collect American antiques on a visit to his friend Electra Havemeyer Webb at Shelburne in Vermont the previous year, H. F. was set on an American-style house. He picked the firm of Cross & Cross of New York, the architects who designed Webb’s “Brick House.” Woodwork purchased by du Pont in 1925 from an eighteenth-century house in Chestertown, Maryland, inspired the name of his new summer residence. Henry Davis Sleeper helped to create the interiors while Marian Coffin created the landscape. H. F. du Pont never did things in a small or lackadaisical way. Every detail, every piece of furniture, each window treatment, was carefully chosen with regard for color, symmetry, and overall effect.

On August 4, 1926, the du Ponts moved into their new summer house. With fifty rooms, including nine bedrooms and eleven full bathrooms, Chestertown House was not your typical seaside home. Photos of the interiors and the terraced lawn looking out to the Atlantic seem completely in keeping with H. F.’s style, taking into consideration Ruth’s desire for a less-formal house than Winterthur.

Photos of the rooms show they are similar to many other summer houses of the du Pont’s social set. Less high-style furniture and ceramics and more simple pieces of pine or maple, hooked rugs, ship models, quilts, brightly colored ceramics, and pewter. It has often been said that Chestertown was H. F.’s incubator house, where he first experimented with decorating with American objects and an innovative use of color. It became the foundation for Winterthur, and he even considered that someday it might also be a museum. But in 1931, after the major expansion of Winterthur, H. F. began to move some pieces to his Delaware house and eventually, even elements of historic architecture. Now Chestertown was more of a family home—Ruth’s place to get away and relax with her daughters and then grandchildren.

What became of Chestertown House? Despite a brief consideration of selling it in 1933 as the Depression weighed heavily on family finances, they decided to keep it. The house meant summer to several generations of this branch of the du Pont family. With H. F.’s death in 1969, some objects came to Winterthur, many went to his daughters, and others were sold.

The fate of the house thereafter is a fascinating tale. After brief notoriety when it was owned in the 1980s by Baby Jane Holzer, a member of Andy Warhol’s inner-circle, it mutated into Dragon’s Head, a turreted castle complete with a basement shark tank. Obviously, the new owner had a rather different idea than H. F. about what made an attractive summer house. Stripped of most of its historic interiors, it continued to change under subsequent ownership and renaming and eventually was called Elysium.

Fashion designer Calvin Klein purchased the property in 2003 and had Elysium demolished in 2009. He built a new house on the site—a sleek, white modern structure that overlooked the dunes. Some of the few intact elements of historic paneling were removed before the demolition, and an architect working in traditional styles incorporated them into a new house. In 2020, Klein sold the house and land where the du Pont family summer house once sat—then and now a choice piece of property on Meadow Lane—to an unknown buyer for $84 million.

With the holidays fast approaching, ’tis the season of Christmas traditions at Winterthur. The annual Yuletide Tour is under way, showcasing Henry Francis du Pont’s former home decorated for the season. In admiring the lavish dining room at its holiday best, it’s not hard to imagine Henry Francis and Ruth Wales du Pont’s Christmas party guests arriving in Port Royal Circle in an array of luxury automobiles of the latest design and fashion, such as a 1927 Rolls-Royce Phantom I.

Henry Francis and Ruth Wales owned more than 40 luxury vehicles during their lifetime, notably several Cadillacs and three Rolls-Royces, including a Phantom V. Thanks to a generous gift in 2008 from the Philip C. Beals estate of Southborough, Massachusetts, Winterthur is the proud owner of a 1927 Rolls-Royce Phantom I Empress. This exquisite vehicle showcases classic design and engineering elements from the 1920s and 1930s—an important era in the Winterthur story that helped shape the country estate as we know it today.

This fall, Winterthur’s beloved Empress won “Best in Class” at the 9th Annual St. Michaels Concours d’Elegance in Cambridge, Maryland. The Concours featured rare pre-war grand classics with European coachwork, wood-bodied cars, and significant sports cars to 1965 as well as fashion and wooden speedboats.

Distinguished within a class of pre-war open cars, Winterthur’s Phantom I was recognized for its elegant design, superlative condition, and well-documented provenance. Sporting a Brewster green body with polished aluminum trim, black fenders with ivory pinstriping, light green wheels, a light cloth top, medium-brown leather upholstery, and a wood dash, the Empress captured audiences’ attention at St. Michaels. Additionally, it successfully participated in a nonjudged 60-mile tour along the Eastern Shore of Maryland, traveling with 30 other historic automobiles from the St. Michaels Concours event. A Winterthur team comprises members of the Winterthur’s conservation, registration, facilities, and public programs departments that oversee the care and display of the car, making it possible for it to participate in such prestigious invitationals.

Since its founding as a British motorcar company in 1904 by Charles Rolls and Henry Royce, Rolls-Royce has established itself as an icon of automobile engineering and luxury across the globe. By the 1910s, Rolls-Royce was struggling to keep up with American demand. A lucrative American market, high U.S. duty taxes on imported cars, and the long shipment time needed for vehicles to cross the Atlantic prompted the incorporation of Rolls-Royce of America, Ltd., with the first American plant opening in Springfield, Massachusetts, in 1919. Silver Ghosts were the first Rolls-Royces produced on the Springfield assembly line, and the Phantom series began shortly thereafter in 1926. The impact of the Great Depression demanded a scale back in production causing the plant to close by 1931. The 1,140 Springfield-built Phantoms are the only Rolls-Royce motorcars that were built outside of the United Kingdom.

The Empress’s story began at that very same Springfield plant with its manufacture in 1927—well before its arrival at Henry Francis du Pont’s country estate. While the chassis was constructed by Rolls-Royce of America, the body was built by the Brewster Company—a Long Island coachwork company that Rolls-Royce of America purchased in 1926 to ensure the highest standards of body fabrication for its vehicles. Brewster was the coachbuilder of choice for many wealthy Americans, such as the Vanderbilts, the Rockefellers, and the du Ponts. As early as 1922, Henry Francis had his Cadillacs fitted with Brewster bodies. The Empress was first fitted with a Brewster Lonsdale-style sedan body but was later fitted with a Brewster Ascot body. The practice of changing out bodies on Rolls-Royces and other luxury automobiles was common during this era.

As a result, there are only 28 recorded Phantom I vehicles with this Ascot body, and Winterthur’s is one of them.

Thanks to a well-documented provenance, the Empress’s ownership can be traced from its manufacture to its arrival at Winterthur in 2008. Shortly after her debut in Springfield, Henry G. Lapham of Brookline, Massachusetts, purchased her new in 1928. The Lapham’s 32-acre residence and gardens designed by the firm of Fredrick Law Olmstead (the head architectural firm that designed the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair) was in many respects similar to the country estate setting of Winterthur. In 1936, Lapham traded the Phantom I to Packard Company of Boston. That same year RE Clark, Inc., purchased the vehicle for $250. In 1940, Frederic J. Shepard II (“Fritz”) of West Newton, Massachusetts, purchased her from RE Clark, Inc. Phillip Beals of Southborough, Massachusetts, was the squadron mate of Fritz’s son, Fredrick J. Shephard III (“Eric”), in the U.S. Navy during World War II and became a close friend of the Shepard family. Through this relationship, Phillip Beals became aware of the Shepard’s 1927 Phantom I and eventually bought the vehicle in 1947 for $600 after a brief ownership by Dr. Robert C. Seamons of Marblehead, Massachusetts. The Beals family owned the Phantom I for more than 60 years, including it in their estate gift to Winterthur in 2008.

May 2016 will mark the 10-year anniversary of the Winterthur Invitational—an annual historic auto display that celebrates the finest automobiles of the country-estate era. The du Pont family and the Brandywine Valley have long been associated with the automotive era of the early 20th century, from the building of early roads to Alfred I. du Pont owning the second automobile in the state of Delaware. Winterthur looks forward to welcoming visitors to the Coach House in May to meet the Empress and learn more about historic automobiles from the 1920s to 1960s. Stay tuned this spring for more information about the Winterthur Invitational.

Post by Chase Markee, Administrative Assistant, Academic Programs

Sources:

Landrey, Gregory J., Director, Library, Collections Management & Academic Programs

Rolls-Royce in America, Rolls-Royce Foundation. Accessed December 2, 2015. http://rollsroycefoundation.org/rolls-royce-in-america.html.

St. Michaels Concours d’Elegance, accessed December 1, 2015. http://smcde.org/index.html

The upcoming Bank to Bend event on March 9 celebrates the snowdrops on the March Bank, which also features winter aconites, snowflakes, and crocuses—and this year, because of the mild weather we are already seeing daffodils, scilla, and squill popping through the leaf litter. One of the questions that comes up often but that I am always a little hesitant to answer is, “How many bulbs are there in the March Bank?” I always say millions, with my fingers crossed behind my back because, after all, I have not counted them.

I finally decided to resolve this nagging doubt. Using Google Earth, I plotted the area of the March Bank, following the general boundaries of the area that we used for its restoration, but decreased them slightly. I drew a line from the Scroll Garden to the 1750 House, then over to Magnolia Bend, but I excluded the Glade. The area enclosed by this measurement is 6.9 acres, or 300,564 square feet.

Looking at one square foot of the March Bank, I chose an estimate of 10 bulbs per square foot. This number is very conservative—some areas have as many as 40–50 bulbs in a square foot, whereas others have only a few or no bulbs, including the paths and watercourses. So, 10 is probably a fair guess.

Next, I multiplied 300,564 (the number of square feet) by 10 (the average number of bulbs per square foot) and got 3,005,640 bulbs. Even if my assumptions are off by half, it would still be more than a million bulbs. I propose that saying the March Bank has “millions of bulbs” is well within the margin of error.

Please join us on March 9 to see these beautiful bulbs for yourself on a guided or self-guided walk.

Post by Chris Strand, Charles F. Montgomery Director and CEO of Winterthur

The 175 rooms in the house have a variety of flooring that must be maintained, with the vast majority made up of wood boards. Their width varies greatly, from two or three inches to those in the Maple-Port Royal Hall that measure 24½ inches wide! Some boards have changed over time, warping or loosening slightly, squeaking with every footfall. Several parquet floors remain, including in the Empire Parlor, which you can see on the self-guided Introductory Tour.

Visitors might assume that, at some point, the floors must have been coated with some special material to take the beating of hundreds of footsteps traveling across them—perhaps a low-maintenance substance like polyurethane. In reality, the floors are cleaned by a method that has remained almost unchanged since the museum’s first visitors walked the halls and, quite possibly, even before. It is the simple process of applying a paste wax, then using a buffing machine and brush, to what seems like miles of wood flooring.

At least twice a year, the floors of the main tour route, receive a fresh coat of wax. The smell is pungent and distinct, and the wax leaves the floor extremely slippery prior to drying. After being applied across the grain, it is left to dry with the aid of fans for several hours before being “taken up” with the buffing machine and a clean brush. The result is a glossy yet soft shine and a protective, water-resistant layer.

As people walk along the tour, they sometimes leave scuffs and dirt behind and may even take a tiny amount of the wax with them on their shoes. The wax is gradually worn away and the shine dulls. To maintain the polish and keep the floors clean of soil and debris, the same electric floor buffers, again with a stiff-bristle brush attachment, are run across the boards, this time with the grain. We do this daily in higher-traffic areas and monthly or yearly in areas that are seldom toured.

Eventually it’s time to start the process all over again, continuing the tradition of rejuvenating Winterthur’s floors. Wax on, wax off, buff as needed.

Post by Matthew A. Mickletz, manager, preventive conservation.